Dimensions of Understanding in AI/ML Roles

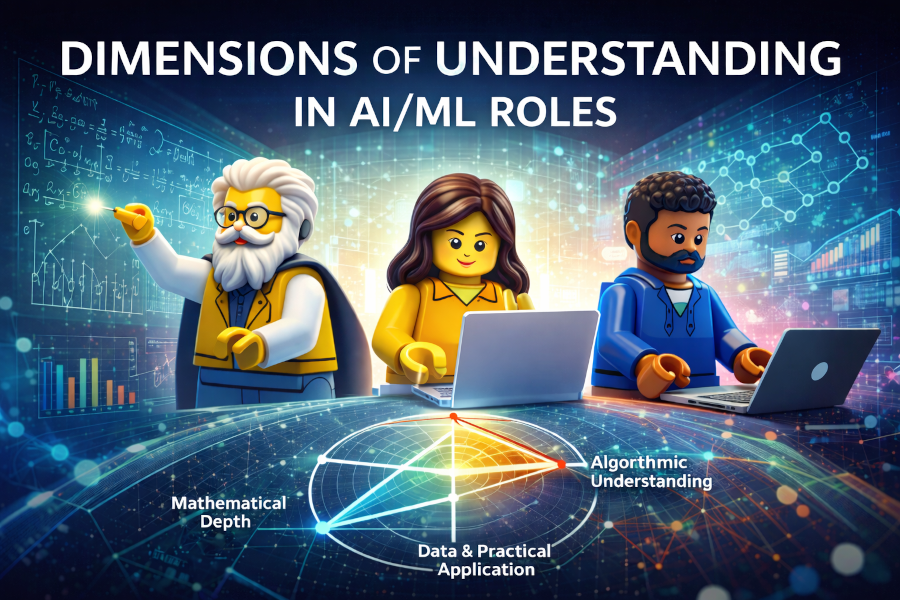

A multi-dimensional view of AI/ML roles, exploring how mathematicians, data scientists, and engineers understand and contribute to AI at different levels.

Over the past two years, I have been immersing myself in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning through books, articles, and conference videos. I’ve tried to explore AI/ML at multiple levels: from the mathematics to the algorithms, and from emerging protocols to architectural patterns. While I am still on this learning journey, my current focus is on data, the foundation of AI/ML, and how it drives insights.

Discussions around AI and Machine Learning roles often drift toward hierarchy: who really understands AI? In practice, this framing is misleading. Understanding in AI is multi-dimensional, and different roles are optimized for different kinds of depth.

This article explores three common roles, Mathematicians (ML theorists), Data Scientists, and AI/ML Engineers, not as ranks, but as positions in a space of complementary expertise. Rather than asking who knows more, we ask: what kind of understanding does each role require?

While this topic has been explored many times, I want to share my own perspective to highlight that AI/ML can be approached at different levels. In practice, the breadth of the field makes it nearly impossible for a single person to cover all dimensions of understanding.

The Three Roles in Context

As mentioned before, there are three roles within the AI/ML landscape.

Mathematicians / ML Theorists work close to the foundations of learning. Their focus is on formal models, optimization, generalization, and the creation or rigorous analysis of algorithms. They operate largely independent of specific datasets or production constraints, aiming instead to expand what is theoretically possible or explain why existing methods work.

Data Scientists operate at the intersection of data, algorithms, and domain knowledge. Their goal is to extract insight, make predictions, and support decisions. They rarely invent new algorithms, but they understand how algorithms behave, what assumptions they encode, and how data characteristics influence outcomes.

AI/ML Engineers focus on turning models into reliable and scalable systems. They treat models as components within larger software architectures and are primarily concerned with integration, performance, robustness, and cost. Their success is measured not by insight or theory, but by whether an AI-powered system works in the real world.

Dimensions of Understanding

Understanding AI/ML is not unidimensional. It is composed of multiple, partially independent dimensions, each capturing a different way of reasoning about learning systems, from mathematical foundations to data interpretation, from algorithmic behavior to system design.

The sections below explore these dimensions and how the three roles emphasize them differently.

Mathematical Depth

Mathematical depth refers to the ability to reason formally about learning systems: deriving objectives, analyzing optimization dynamics, and proving properties such as convergence or generalization.

Mathematicians operate at the highest level of mathematical depth. They work with abstractions such as vector spaces, loss landscapes, and probabilistic bounds, and often contribute new theoretical insights or algorithms. At this level, concepts such as vectors and vector spaces are not just implementation details but the language of reasoning itself. Distances and similarities are expressed through metrics and norms, optimization unfolds over high-dimensional spaces, and properties of models are often analyzed via linear algebra tools such as eigenvalues and eigenvectors. These abstractions help explain stability, convergence, and representational capacity in ways that empirical observation alone cannot.

Data scientists usually possess a conceptual and statistical understanding of the mathematics. They know what loss functions, regularization, and model complexity do, and how these elements affect results, but they typically do not engage in formal derivations or proofs. Data scientists often reason with these mathematical concepts, for example, interpreting embeddings as vectors or distances as similarity, without needing to derive or prove their underlying properties.

AI/ML engineers often rely on mathematical abstractions provided by frameworks. Their understanding is usually sufficient to configure, debug, and reason qualitatively about models, but deep mathematical analysis is not central to their role.

Algorithmic and Mechanistic Understanding

This dimension captures how well someone understands what happens inside an algorithm during training and inference.

Mathematicians approach this mechanistically through formal models and proofs.

Data scientists often develop an equally deep, but more empirical understanding: they know how hyperparameters influence behavior, how models fail, and how different algorithms respond to real data.

AI/ML engineers typically engage with algorithms at a higher level of abstraction. They understand expected behaviors and failure modes, but their interaction is mediated by APIs and tooling rather than mathematical inspection.

Data and Statistical Understanding

Here lies the core strength of data scientists. This dimension includes understanding data generation processes, bias, variance, leakage, causal relationships, and experimental design.

Data scientists are trained to question whether a signal is real, whether a metric is meaningful, and whether a model’s performance will generalize.

Mathematicians may engage with data in abstract or simulated forms.

AI/ML engineers often focus on data availability, pipelines, and quality rather than statistical validity. Their primary concern is ensuring that data can be reliably collected, transformed, and delivered to models for training and inference at scale. While they must be aware of data semantics and basic statistical assumptions, deeper questions about meaning, bias, or causal interpretation typically lie outside their core responsibility.

Software and Systems Understanding

Software engineering depth determines whether AI models become usable systems. This includes code quality, reliability, performance, deployment, monitoring, and long-term maintainability.

AI/ML engineers dominate this dimension. Their understanding is expressed through system design choices: how components interact, how failures are handled, and how performance degrades under load. They design systems that must survive scale, latency constraints, partial outages, data drift, and changing requirements over time.

In this context, models are not isolated artifacts but moving parts within larger systems. Engineering decisions around caching, batching, fallback strategies, observability, and cost control often have a greater impact on real-world behavior than marginal improvements in model accuracy.

Increasingly, this systems understanding includes familiarity with emerging AI-specific protocols and interaction patterns. Concepts such as Model Context Protocols (MCP), agent-to-agent communication, and orchestration mechanisms define how models, tools, and services exchange information. For AI/ML engineers, understanding these protocols is less about model internals and more about establishing reliable, observable, and composable system boundaries.

Data scientists often operate in experimental environments with moderate engineering rigor, while mathematicians typically have minimal involvement in production systems.

Architecture and Integration

Modern AI systems are rarely just models. They are pipelines composed of data ingestion, training, evaluation, serving, retrieval, orchestration, and monitoring, often spanning multiple services and teams.

AI/ML engineers specialize in this architectural view. They reason about how models are composed with data sources, feature stores, vector databases, APIs, and downstream applications. Their focus is on defining clear boundaries between components, selecting appropriate interaction patterns, and ensuring that systems remain modular and replaceable as models, data, or requirements evolve.

In this perspective, models are treated as interchangeable components rather than central artifacts. Data scientists usually engage with parts of the pipeline relevant to experimentation and evaluation, while mathematicians focus almost exclusively on isolated algorithmic components.

Tooling, Frameworks, and Protocols

As AI systems have become more abstracted, familiarity with frameworks, APIs, and emerging protocols has become a form of expertise in its own right. Modern AI development often involves working several layers above raw algorithms, relying on standardized interfaces and managed platforms to compose complex behavior.

AI/ML engineers typically stay closest to this ecosystem. They understand not only how to use tools and frameworks, but what assumptions and trade-offs those abstractions encode. Choices around training frameworks, serving stacks, orchestration tools, and communication protocols directly affect performance, reliability, cost, and debuggability in production systems.

Data scientists maintain working knowledge of these tools to support experimentation, reproducibility, and evaluation. Mathematicians may use software instrumentally to test ideas or run experiments, but they rarely engage deeply with platform-level abstractions or evolving interaction protocols.

Goal Orientation

Perhaps the most important difference between these roles lies in why they exist.

Mathematicians seek to expand theoretical understanding and long-term capability by developing new mathematical frameworks, optimization methods, and learning principles. Their work can lead to entirely new classes of models, training techniques, or guarantees that make previously impossible systems feasible or more reliable.

Data scientists aim to produce valid insights and predictions from data. Their focus is on ensuring that models are grounded in reality: that signals are meaningful, assumptions are explicit, and results generalize beyond the data at hand.

AI/ML engineers aim to deliver reliable AI-powered systems. Their success is measured not by novelty or insight alone, but by whether AI solutions function robustly over time within real-world constraints.

These goals shape every other dimension of understanding.

Dimensional Summary (At a Glance)

The following table provides a compact, visual synthesis of the dimensions discussed above. These dimensions frequently overlap in practice, but roles tend to cluster around different peaks depending on their goals and responsibilities.

| Dimension | Mathematicians / ML Theorists | Data Scientists | AI/ML Engineers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical depth | Very high (formal, theoretical) | Medium (conceptual, statistical) | Low–medium (qualitative) |

| Algorithmic understanding | High (proof-based) | High (empirical, behavioral) | Medium (API- and abstraction-based) |

| Data & statistical reasoning | Low–medium | Very high | Medium |

| Software & systems | Low | Medium | Very high |

| Architecture & integration | Low | Medium | Very high |

| Tooling & protocols | Low | Medium | High |

| Primary goal | Knowledge expansion | Insight & prediction | Reliable AI systems |

A useful mental model is to imagine each role as a radar chart across these dimensions: no role dominates all axes, and none needs to.

How LLMs Are Reshaping the Landscape

Large Language Models (LLMs) have amplified abstraction across the AI stack. Many applications now require less direct engagement with algorithms and more focus on system design, evaluation, and integration.

This shift increases the importance of architectural and engineering understanding while concentrating deep mathematical work into smaller, specialized groups. At the same time, data understanding and evaluation become more critical, as model internals are increasingly opaque.

LLMs do not eliminate the need for theory; they change where it lives and who needs it.

Conclusion

Understanding in AI/ML is not a single ladder to climb but a space to navigate.

Progress emerges because:

- mathematicians expand what is possible.

- data scientists determine what is valid and meaningful.

- AI/ML engineers turn ideas into real-world impact.

AI/ML advances not when everyone understands everything, but when each role understands what it must, deeply enough.